If you’re reading this, you’re probably already using some LLM for coding. Maybe it’s Copilot, maybe Claude Code, maybe Cursor with Gemini enabled (or Cursor’s own model).

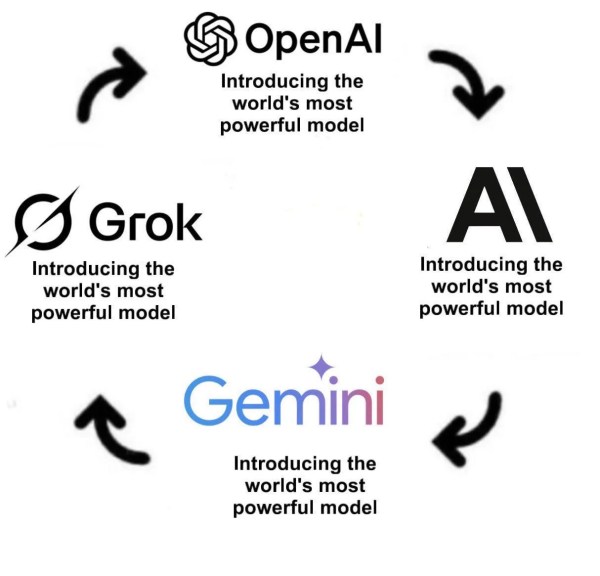

You know the drill. Do you truly expect the announcement “We are worst than competitors?”

The problem is that when someone asks, “Which model is best for Java?”, most answers are based either on a vibes check and opinions, or on re-published benchmarks that, frankly, hardly anyone truly understands – especially what they actually test and how that translates to everyday engineering work.

Today, we’re changing that. We’ll walk through how LLM benchmarking for code actually works, which models are available on the market at the end of 2025, and – most importantly – how they perform in benchmarks that are specific to the JVM, including Java, Kotlin, and Scala.

How Do You Even Measure an LLM’s Ability to Write Code?

The Evolution: from “Can You Code?” to “Can You Be an Engineer?”

The history of LLM coding benchmarks is a story of steadily rising expectations. It all started with a very basic question: can the model generate working code at all?

HumanEval described in the paper Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code is the foundation of almost everything that came afterward. It consists of 164 hand-written Python problems, each with a set of unit tests. The model is given a function signature and a docstring and must generate the function body. Sounds simple? In 2021, even GPT-3 struggled with it.

The key innovation of HumanEval was the pass@k metric. Instead of measuring textual similarity (like BLEU score), we check whether the generated code actually passes the tests. This is a fundamental shift in thinking: we don’t care whether the code looks good – we are interested whether it works.

So what’s the problem with HumanEval? It’s too easy. By the end of 2024, top models were achieving 90%+ on this benchmark. When all the leading models cluster around 90%, it becomes very hard to say which one is actually better.

A similar alternative to HumanEval is MBPP (Mostly Basic Python Problems) – 974 entry-level problems. More data, but roughly the same level of difficulty.

The Modern Standard: SWE-bench

The real revolution arrived with SWE-bench (Software Engineering Benchmark). Instead of asking a model to fill in a missing function or solve an isolated coding puzzle, SWE-bench puts it in a situation that looks much closer to real work. The model is given the full source code of a real GitHub repository, along with the description of an issue taken directly from GitHub Issues, and is asked to produce a patch that actually fixes the problem.

At this point, we’re no longer testing whether a model can “code” in the narrow sense. We’re testing whether it can behave like a software engineer. To succeed, the model has to understand an existing codebase, navigate across multiple files, and reason about how different components interact. It needs to interpret the often messy, incomplete, or ambiguous business context hidden in an issue description, follow the project’s established conventions, and produce a change that solves the problem without breaking existing tests. This is software engineering, not algorithm trivia.

SWE-bench Verified raises the bar even further. It is a curated subset of 500 tasks that have been manually verified by humans, and it has effectively become the industry’s gold standard. When vendors talk about their models’ real-world coding capabilities, this is the benchmark they usually point to.

However, SWE-bench also has a fundamental limitation. It is exclusively focused on Python, which immediately makes it less useful for large parts of the industry. On top of that, it has been around long enough that there is a growing suspicion that some models may have been trained on it, at least partially. That doesn’t make the benchmark useless, but it does mean we should treat impressive scores with a healthy dose of skepticism – especially if we care about JVM languages like Java, Kotlin, and Scala.

What’s particularly striking about SWE-bench is the scale of the solutions it expects. The mean lines of code per solution is just 11, with a median of only 4 lines. Amazon’s analysis found that over 77.6% of the solutions touch only one function. This tells us something important: SWE-bench is testing surgical precision on isolated problems, not the kind of sprawling, multi-component changes that often dominate real engineering work. Additionally, over 40% of the problems come from the Django repository alone, which introduces significant bias toward one project’s patterns and conventions.

Additionally, as it has become the most widely recognized, it regularly appears in new model announcements and marketing materials. The results are… interesting 😁

Scale AI has attempted to address these limitations with SWE-bench Pro, a significantly improved successor.

Instead of 500 Python-only problems, it offers 1,865 tasks drawn from 41 repositories across Python, Go, JavaScript, and TypeScript. The solutions are substantially larger – averaging 107 lines of code with a median of 55 lines, typically spanning 4 files. The benchmark also covers a more diverse range of software types: consumer applications with complex UI logic, B2B platforms with intricate business rules, and developer tools with sophisticated APIs. Crucially, humans rewrote the problem descriptions based on issues, commits, and PRs to ensure no missing information, and they added explicit requirements grounded in the unit tests used for validation. All environments are dockerized with dependencies pre-installed, so the benchmark explicitly does not test repository setup – just the engineering work itself.

New Benchmarks: BigCodeBench and LiveCodeBench

BigCodeBench emerged as a response to the growing criticism that existing coding benchmarks had simply become too easy. Instead of testing toy problems, it raises the bar by introducing 1,140 tasks that require real interaction with 139 different libraries. On average, each task comes with 5.6 tests and achieves 99% branch coverage. At this level, knowing the syntax is no longer enough. The model needs to understand how to actually use libraries like pandas, numpy, requests, and dozens of others in realistic ways—exactly the kind of knowledge developers rely on in day-to-day work.

LiveCodeBench, on the other hand, tackles a completely different but equally important problem: data contamination. Its tasks are sourced from weekly programming contests on platforms like LeetCode, AtCoder, and Codeforces, and each task is tied to a specific publication date. This allows evaluators to check whether a model could realistically have seen the problem during training. If a model was trained before a given date, it simply couldn’t have memorized that task. In practice, this makes LiveCodeBench one of the most credible attempts so far to measure genuine generalization rather than benchmark recall.

Multilinguality: Where Is Java?

And this is where we get to the heart of the problem. A review of 24 major coding benchmarks reveals a rather uncomfortable statistic. An overwhelming 95.8% of existing benchmarks focus on Python, while only five of them include Java at all.

This imbalance isn’t accidental. Python dominates machine learning research, so benchmarks are naturally designed around the language researchers themselves use every day. The result is a benchmarking ecosystem that tells us a lot about how well models perform in Python, but surprisingly little about their real capabilities in languages like Java – or, by extension, the broader JVM world.

MultiPL-E is an effort to address this imbalance by translating the HumanEval and MBPP benchmarks into 18 additional programming languages, including Java, Kotlin, and Scala.

On paper, this sounds like exactly what the ecosystem needs. In practice, however, there’s a catch. Automatic translation doesn’t always capture the idioms of a given language. A Java test mechanically translated from Python may compile and run, but it often fails to exercise what actually matters in an object-oriented context. Instead of testing real JVM-style design, it may still be implicitly testing Pythonic assumptions.

HumanEval-XL takes a slightly different approach by expanding the benchmark to cover 12 programming languages, including Python, Java, Go, Kotlin, PHP, Ruby, Scala, JavaScript, C#, Perl, Swift, and TypeScript. It also introduces 80 problems written in 23 natural languages, which makes it more diverse than earlier efforts. That said, while it is certainly better than nothing, it still falls short when it comes to evaluating realistic enterprise Java scenarios.

The problems remain small and isolated, far removed from the kinds of codebases and architectural concerns that dominate real-world JVM development.

Aider Polyglot deserves special attention for JVM developers because it actually includes Java. The benchmark consists of 225 hard-level Exercism problems distributed across six languages: JavaScript (49), Java (47), Go (39), Python (34), Rust (30), and C++ (26). Solutions typically range from 30 to 200 lines of code and span at most 2 files. The evaluation allows one round of feedback before final assessment – mimicking a realistic back-and-forth with a coding assistant. While this is far from enterprise-scale Java work, it remains one of the few benchmarks that can tell us anything concrete about model performance on JVM languages in a standardized way.

JavaBench: The First Benchmark Dedicated to OOP

JavaBench is a direct response to Python’s dominance in coding benchmarks. Instead of abstract problems or toy functions, it is built around four real Java projects, covering 389 methods across 106 classes, with an impressive 92% test coverage. The benchmark was additionally validated by 282 students, who achieved an average score of 90.93 out of 100, giving us a meaningful human baseline.

What truly sets JavaBench apart is its focus on object-oriented programming features. It explicitly evaluates concepts such as encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism – areas that benchmarks like HumanEval do not even attempt to measure. This makes it far more representative of how Java is actually used in practice.

JavaBench is nice try, but not the most active supported thing. We have better alternatives at the market.

CoderUJB: Benchmarking Real-World Java Work

CoderUJB pushes realism even further. It is built on 17 real open-source Java projects and contains 2,239 programming questions spanning multiple task types. These include not only code generation, but also test generation, bug fixing, and defect detection. The point here is no longer just to check whether a model can produce syntactically correct code, but whether it can perform the kinds of activities a real Java developer deals with every day.

Brokk Power Ranking: A Java Benchmark for 2025

The Brokk Power Ranking, created by Jonathan Ellis, co-creator of Apache Cassandra, is one of the freshest additions to the benchmarking landscape and directly addresses some of the core weaknesses of SWE-bench. Unlike most existing benchmarks, it is not Python-only. Instead, it draws tasks from real Java repositories such as Brokk, JGit, LangChain4j, Apache Cassandra, and Apache Lucene.

Equally important, it is genuinely fresh. The tasks are derived from commits made within the last six months, which significantly reduces the risk that models were trained on the benchmark data. It is also intentionally challenging, featuring 93 tasks with contexts reaching up to 108k tokens. Ellis positions it deliberately between AiderBench, which tends toward toy problems, and SWE-bench, which often throws entire repositories at the model and says “good luck.”

Results as of November 2025 paint a much clearer picture of how models actually perform in Java-centric, real-world scenarios. At the very top, the S tier is occupied by GPT-5.1 and Claude Opus 4.5, which clearly separate themselves from the rest of the field. Just below them, the A tier includes GPT-5, GPT-5 Mini, and Grok Code Fast 1, forming a strong upper-middle group with solid but slightly less consistent performance. The B tier is represented by Claude Sonnet 4.5 and GLM 4.6, while the C tier includes Grok 4.1 Fast, Gemini 2.5 Flash, Gemini 3 Pro (Preview), and DeepSeek-V3.2. At the bottom, in the D tier, we find Kimi K2 Thinking and MiniMax M2.

Several patterns stand out immediately. Chinese models such as DeepSeek-V3, Kimi K2, and Qwen3 Coder perform noticeably worse here than they do on benchmarks like SWE-bench or AiderBench. This suggests that their apparent strength on more generic or Python-heavy evaluations does not translate well to Java-heavy, object-oriented codebases.

Another clear takeaway is GPT-5’s dominance across every price tier. No matter whether you look at premium or more cost-conscious options, GPT-5-based models consistently lead in terms of raw capability. The trade-off, however, is speed: GPT-5 remains relatively slow compared to its competitors.

Finally, Claude Sonnet 4 stands out for a very different reason. While it does not top the absolute performance charts, it is screaming fast – faster than all models in tiers A and B. For workflows where latency matters as much as correctness, this makes it a surprisingly compelling choice despite not sitting at the very top of the ranking.

Kotlin is in interesting position in one important respect: specialization. Mellum, used inside JetBrains AI Assistant, is currently the only model with dedicated fine-tuning specifically for Kotlin, which gives it a noticeable edge in understanding Kotlin idioms and conventions. Beyond that, Claude models tend to handle Kotlin surprisingly well, especially when it comes to expressive syntax and functional-style constructs.

Scala, unfortunately, remains the most challenging case. No mainstream model has dedicated fine-tuning for Scala, which puts the language at a structural disadvantage. That said, the best reported results so far come from Claude Opus 4.5, which benefits from a strong grasp of functional programming concepts, and GPT-5, which shows solid performance on Scala tasks in benchmarks such as MultiPL-E. These models can be effective, but they still require more guidance and validation than their Java or Kotlin counterparts.

Practical Takeaways

Before diving into model recommendations, it is worth stepping back to consider what benchmarks actually measure – and what they do not. When we say an agent scores 25% on SWE-bench Pro, we are saying: in a problem set of well-defined issues with explicit requirements and specified interfaces, 25% of the agent’s solutions pass the relevant unit tests. This is useful for tracking progress, but it is not software engineering as most practitioners understand it. The high-leverage parts of real SWE work – collaborating with stakeholders to develop specifications, translating ambiguous requirements into clean interfaces, writing secure and maintainable code – remain entirely unmeasured. We know the code passes tests; we have no idea if it is maintainable, secure, or well-crafted. The UTBoost paper goes further, demonstrating that many SWE-bench solutions pass unit tests without actually resolving the underlying issues. Keep this gap in mind when interpreting any benchmark results.

When choosing a model, the most important rule is not to trust any single benchmark blindly. SWE-bench, while influential, is Python-only, and HumanEval is simply too trivial to say much about real-world engineering in 2025. Benchmarks that span multiple languages- such as Aider Polyglot or the Brokk Power Ranking – are far more informative for JVM developers. Even then, no benchmark can replace testing a model directly on your own codebase, with your own architectural constraints and conventions.

Looking at broader trends for 2025, Java is finally starting to receive more focused attention. The emergence of JavaBench, CoderUJB, and the Brokk Power Ranking is a clear signal that the ecosystem is moving beyond Python-centric evaluation. At the same time, specialized models are becoming more prominent, with Mellum for Kotlin and tools like Codestral for code completion pointing toward a future of narrower but deeper optimization. Another clear pattern is that reasoning increasingly matters: models with explicit “thinking” or extended reasoning modes tend to perform better on complex, multi-step tasks. Context size also plays a critical role, with models like Gemini 3 Pro – offering up to one million tokens – making it feasible to work with entire codebases in a single session.

There are also some pitfalls worth actively avoiding. “Benchmark gaming” is becoming more visible, particularly when models show suspiciously strong results on a single benchmark like SWE-bench but fail to replicate that performance elsewhere. Relying on outdated benchmarks is equally misleading—HumanEval from 2021 tells us very little about model capabilities in 2025. Finally, one-off tests are unreliable by nature, since LLM performance is probabilistic. Meaningful evaluation requires repeated runs and consistent patterns, not a single lucky output.

So, the state of LLM benchmarking for JVM languages in 2025 is… complicated. Python still dominates research and evaluation, but genuinely JVM-focused benchmarks are finally emerging, especially for Java, with Brokk Power Ranking leading the way. Kotlin benefits from an steward in JetBrains and experiments like in Mellum, while Scala is still waiting for truly dedicated tooling.

For everyday development work, Claude Sonnet 4.5 and GPT-5 are both safe, well-rounded options that handle the vast majority of typical tasks reliably. When the work shifts toward long, complex debugging sessions – where reasoning across many files and iterations really matters – Claude Opus 4.5 clearly pulls ahead. On the other end of the spectrum, if speed and cost efficiency are the primary concerns, lighter models such as Gemini 2.5 Flash or GPT-5 Mini offer a reasonable trade-off between performance and latency.

Note for the end: The difficulty of designing good benchmarks… actually makes me optimistic about coding agents. Current state-of-the-art benchmarks fall woefully short of capturing the nuance and messiness of real engineering work – yet the agents we have are already remarkably capable. There is substantial low-hanging fruit in benchmark design: validating with property-based testing instead of unit tests, using formal methods where possible, starting from product-level documents like PRDs and technical specifications, and creating benchmarks that test information acquisition and clarification skills rather than assuming perfect problem statements.

As these improvements arrive, we should expect corresponding improvements in agent capabilities through better training signals.

Please remember, the current solutions are the worst we will ever get 😊

Author: Artur Skowronski

Head of Java & Kotlin Engineering @ VirtusLab • Editor of JVM Weekly Newsletter